David Hepworth expresses his appreciation of a unique talent, live and on record, all the way up to Bob Marley’s 36 year old exit from the world and immortal legacy. Play all summer long.

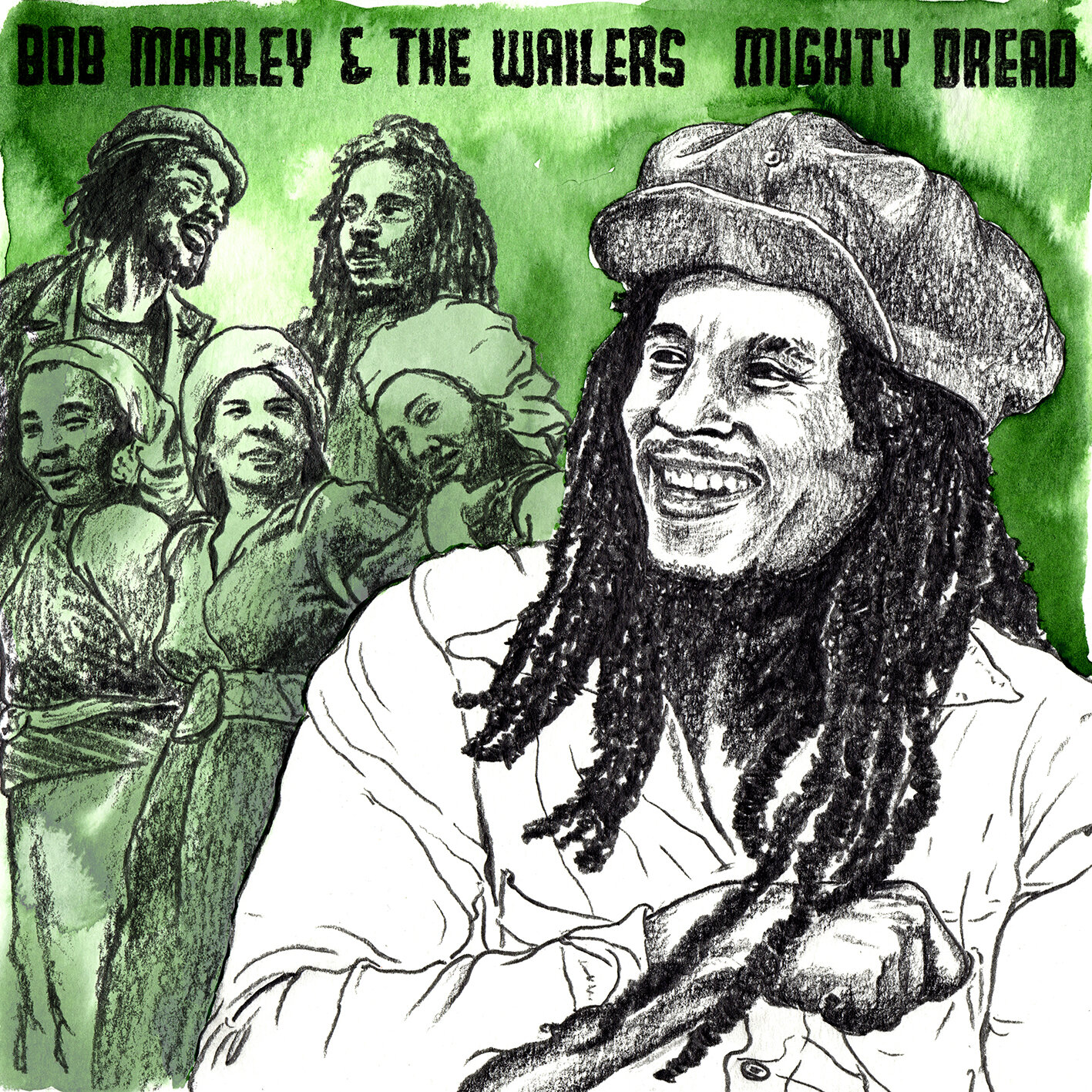

Words & curation by David Hepworth, cover art by Mick Clarke, as ever

It was hot that night in July of 1975. A night so hot in fact they rolled back the roof of the Lyceum so we could see the open air. The first time the Wailers had come to Britain, in the winter of 1972, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston had been so disturbed by the unfamiliar sight of snow they cut their dates short and went home. By the time 1975 came round those two had departed, it was now clearly Bob Marley’s group and the weather was closer to what they would have been used to at home. Which was only right. Most musicians bring just their songs to the stage. Others bring a whole world with them.

The announcer promised we were in for “the Trenchtown experience”. The whiter we were and the further removed from the realities of life in this part of Kingston, Jamaica, which would now be described as deprived and would then have been called a slum, the more thrilling that promise seemed. Of course by then Bob Marley had done well enough in Jamaica and had seen his songs taken into the pop charts by the likes of Johnny Nash not to actually live there but he looked the part of street fighter and he sang of road blocks, of curfews, of shooting the sheriff without once letting the mask slip enough to suggest any of it could be a put-on.

The thing that separates the greats - Elvis, Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, James Brown and Bob Marley for instance – from the rest is that first and foremost they are their own greatest creations. They have musical gifts, of course, but what makes them exceptional is that they play themselves so perfectly it’s impossible to detect where the reality ends and the act begins. A million actors can imitate Al Pacino but the person who invented the act was Al Pacino. It was much the same with Bob Marley.

As his band unfurled one sinuous groove after another, each played with the kind of nonchalance that only comes from prolonged study, and the I-Threes swayed from side to side, Marley high-stepped on the spot like a man engaged in higher business than simply entertaining an audience. And yet beneath it all he never seemed remotely in danger of missing any of his marks. The greatest compliment you could pay any of it was that at no point did it seem like a performance.

It’s impossible to go anywhere in London forty years later without hearing some busker singing “No Woman No Cry”. This is a testament not only to the popularity of that one song but also to the fact that most musicians don’t recognise that Marley’s original performance of that song was so imbued with his divine heaviness, so tinged with his infectious spirituality, so calm at its centre, that it rendered further versions beside the point. This is the secret sauce of greatness in popular music that is so often lost sight of in the excessive analysis of song writing. It’s not what they do. It’s the way they do it.

The first thing is the voice. Nobody ever talks about Marley’s singing, probably because he didn’t go in for showy displays of melisma, but his singing was key. His voice was one you had no problems living with. He could deliver harsh Biblical words - hypocrites, exodus, tribulation - in a way that those words fell gently on the ear. “One good thing about music,” as he sang. “When it hits you feel no pain.”

Island Records’ Chris Blackwell, who mixed his records for the rock market, correctly identified the fact that his voice was the perfect frequency to announce itself on the radio. It should never be forgotten that Bob Marley was a huge, chart-busting pop star before he was a Third World Icon.

The second thing is the playing. It’s not virtuosic because that would be beside the point. It is however the playing of musicians who are appreciative of the fact that music is the thing that occurs in the spaces between their individual contributions and are therefore listening to each other with due respect for that fact. It’s probably no coincidence that he was all over the charts and the radio at a time when the charts were dominated by disco and punk, neither of which were rhythmically very interesting. Marley’s magic is there in the bass figure on which “Crazy Baldhead” leans. It’s there in the uniquely rousing guitar that drives “Exodus” and that un-trackable bass drum sound on “Natural Mystic”. All through this playlist there’s a mad playfulness at work. It’s there in the fact that every thing he did you could dance to. I doubt if he ever had a conversation with anyone about whether a track was danceable because the notion that people should be able to get joy from dancing to his music was so hard-wired into him it didn’t need saying.

He died in 1981 at the age of 36, thereby avoiding the main destroyer of reputations, which tends to be the music people make when they’re trying to get back to their best and don’t quite know how to do it. He was fortunate in his times. He was a creature of the analogue age and never had to contend with click tracks and the snap-to-grid music of the electronic age. Everything on his records was played by a human and sounds like it. And pretty much everything he made, no matter if he was trying to get a woman to come across or smiting the unrighteous with the rod of correction sounds as though it was animated by the joy of making music.

In popular music an early death often confers sainthood, which Marley was no more deserving of than any of us. Like every rock star that made it he cooked up rationales to justify his enjoyment of the rewards. He bought a BMW because the words stood for “Bob Marley [& the] Wailers” (or was it “black man’s wheels”?). He left his wife for a beauty queen. He was no wiser than any of us. Much of the wisdom he put into the world came from the bible stories he learned in his childhood. He put those stories together with tunes that, thanks to the way he did them, seem to sing themselves. You don’t actually have to play the tunes that follow. Look at the list and then close your eyes. You can hear them in your head. This is all the memorial any musician needs.

David Hepworth is an author and broadcaster, discover more at http://www.davidhepworth.com/

Pre-order Cedella and Bob Marley’s forthcoming book Redemption