Since the news of Pitchfork “folding” into GQ magazine in early January, a few people have asked me what I think about it. I’ve read a few of the eulogies and share the sad sentiment of most of them, but I’m generally more optimistic about the role and future of music writers. Sort of. Here, I’m summing up five ways in which music writing can survive (and by that, I mean thrive) and I mention a few of my own favourite music editorial brands.

We cannot put the genie back in the bottle when it comes to the commercial viability of music magazines. Pitchfork was really the last music media ‘empire’. It grew from a humble blog into a multi-revenue music media business, eventually succumbing to an acquisition by an unlikely mothership in Conde Naste, at a time when that company desperately needed ‘digital first’ media properties.

No other music media brand has succeeded on any significant scale since.

The short version of the story is that Pitchfork had its day. Its heyday lasted well over a decade - not a bad run, even compared with legendary music media brands of the golden age of music journalism, like Rolling Stone or NME. Pitchfork’s digital presence made it more than just an editorial brand, however. It became a destination for music lovers, aficionados and obsessives, and eventually outgrew its original “white male hipster” tone of voice to become more inclusive and diverse.

And then got a bit too big for its boots. In some cases it became a concern for artists that had been “built on Pitchfork” (with famous 8.something review scores) but who could also be then subsequently marked down, or snubbed altogether. Mind you, the point of music media coverage is that it cannot keep on writing about every artist, but be a curated source of discerning taste and discovery - and perhaps more importantly - a way of enjoying a deeper connection to music and artists. But those infamous review scores (still a central feature of Pitchfork even now) matter much less in today’s music economy. As reviews waned in relevance, all of Pitchfork’s various income streams probably just withered away gradually.

So now, can “niche” media thrive? In music’s case, it looks unlikely, some examples of music brands I like: She Shreds, a ‘magazine’ built around the growing community of female guitarists, is a great concept, but seems to have struggled to find a solid format. At one time, it was a physical magazine but is now essentially a blog with a focus more on YouTube videos (“She Shreds TV”) than the written word. Loud & Quiet seems to have sustained a physical format magazine through a subscription model and merch store - wryly with a strapline ‘moderately successful’. Its “Midnight Chats” podcast seems to have become established as a long-term show.

This first way to succeed then, is to move away from the written word as the central focus, to video or audio (podcast) first. At least that way, there is distribution, by way of the usual giant social media and streaming platforms.

Goldflake Paint, The Quietus and many more - all had moments of relevance (on a much smaller scale than Pitchfork) but could not find viability beyond being blogs with Patreon style funding and a bit of ad revenue (though The Quietus successfully diversified into artist management).

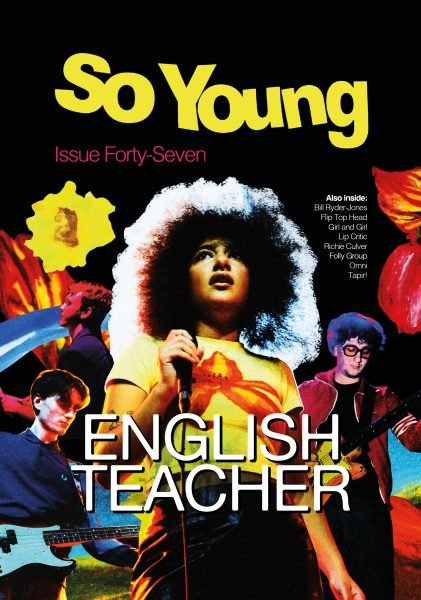

Personally I love So Young. It is a UK-based ‘zine’ built around the resurgence of guitar bands. On a modest scale, it has built a community, subscriber base, (another) cool merch brand, and has branched out into a small label and live music booking agency. If it does well with the artists it represents, and those artists continue to value it and pay back those favours, it could grow into something relevant. It is the commercialisation of a cultural scene. Viable, albeit on a smaller scale. An so here is the second way - quickly build your media brand or zine into a ‘real business’ - talent management or a record label, for example.

So Young Magazine issue 47 cover

Meanwhile, post Pitchfork, what constitutes dream press for an artist? I recently posed this question to Martin Courtney of New Jersey indie ‘stalwarts’ Real Estate and his answer was revealing: “I guess a spread in the New Yorker - something that reached a new and interesting audience for us”.

Well, Sir Lucian Grange is already ahead of the curve on that one. In which case the future of music journalism is perhaps, to be subsumed into broader literary and lifestyle titles. Just like Pitchfork and GQ. And so this is the third way: music writing incorporated within larger media brands, from The New Yorker to Waitrose Weekend magazine (or my favourite, McSweeney’s The Believer music issue). I saw something recently on social media about the imminent relaunch of Q Magazine. Perhaps it should actually be launched as the editorial sub-brand within Amazon Music, Apple Music or even as part of a news media empire (if there are any left).

Meanwhile, film writing seems to have all the same issues as music, but has a few more innovative solutions. After a decade in existence, the music buff app Letterboxd seems to be gaining traction among young audiences beyond aficionados. So this is a fourth way - to mix up pro journalism with UGC and fan community content i.e. go the way of the app. I even tried something similar to this myself with The Song Sommelier (where you are reading this) - having music super fans write and curate alongside professional journalists. It’s still a thing, potentially.

Commercial viability and income streams remain a challenge for all four routes.

But I mentioned a fifth as well I think?

Well, while music journalism suffers chronic illness, you might have noticed that the ‘music business’ is rampant, with major labels making millions of dollars a day. A few years ago Warner Music acquired a media brand (Uproxx). [N.B. just a few days after I wrote this, WMG announced it was effectively jettisoning Uproxx and “owned and operated” media, so I guess this final option is indeed the way to go, as an alternative, read on]. UMG owns the UMusic Media Network, describing it as “a comprehensive media and data offering to uniquely connect brands and partners with exclusive media from world’s largest music company and most iconic and influential artists”.

Even if, like me, you cannot quite figure out what that means, the point is that labels and artists need music press. Artists love to get press - it may be less effective than a playlist add or TikTok viral moment, but it is validation, affirmation, depth. But rather than ‘own’ somewhat compromised media brands, why don’t labels use all their streaming catalogue money to invest in the music media outlets out there? Buy their ads, sponsor some paid content, invest (again UMG recently invested in indie radio network NTS in a low key but important way). While music press should enjoy editorial independence, look around. How much established news coverage and features in national premium news is “paid content”?

So music journalism is able to survive in different forms. It feels like it is possible to create new platforms for music discussion, discovery and enjoyment - perhaps just not in the form of branded multi-feature music magazines.

The Art of Longevity podcast Season 9 preview with Real Estate, is out released in early February 2024.